Special Autonomy is widely regarded as a failure, but its impact on Papua’s schools has been even worse than expected

Bobby Anderson

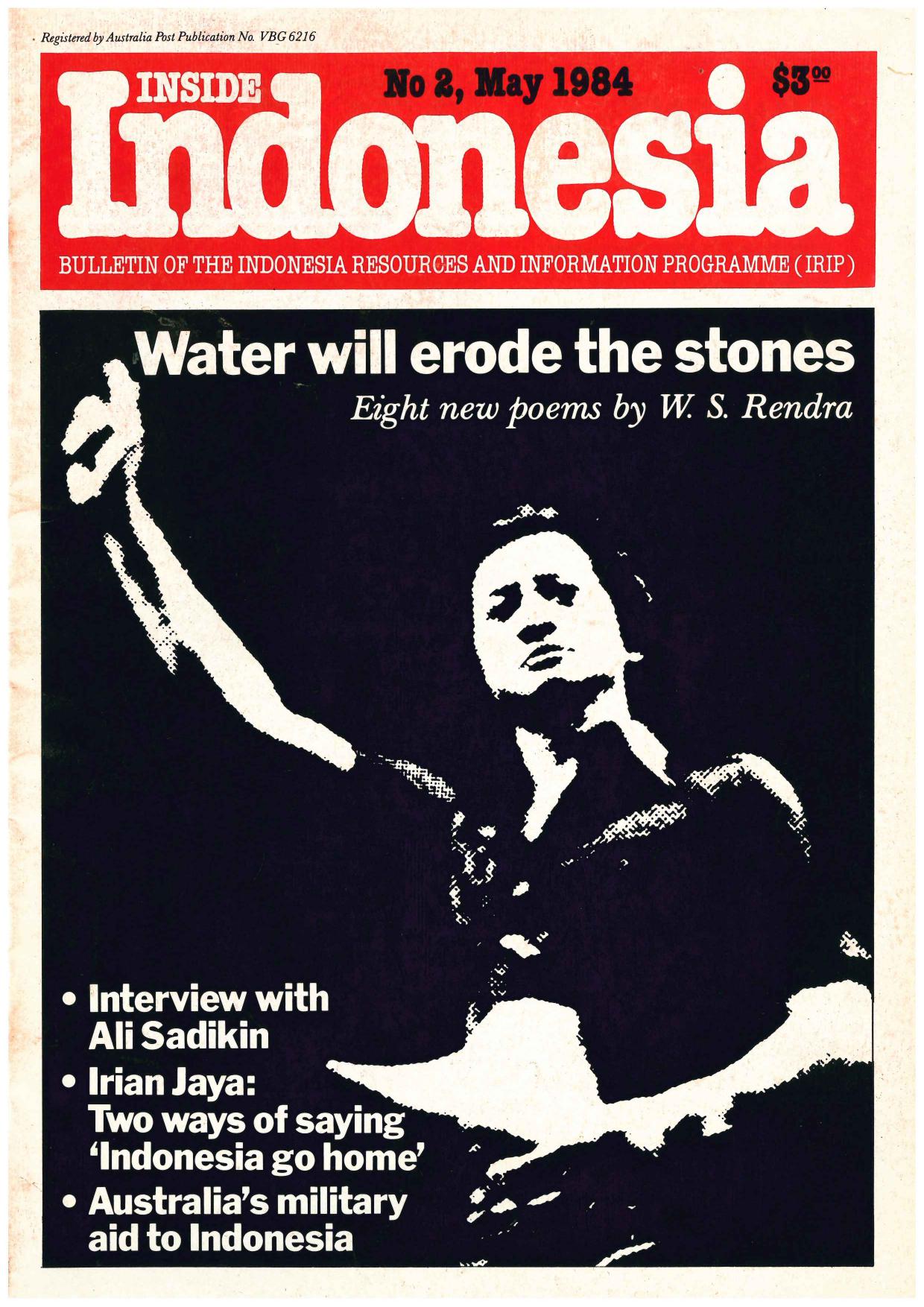

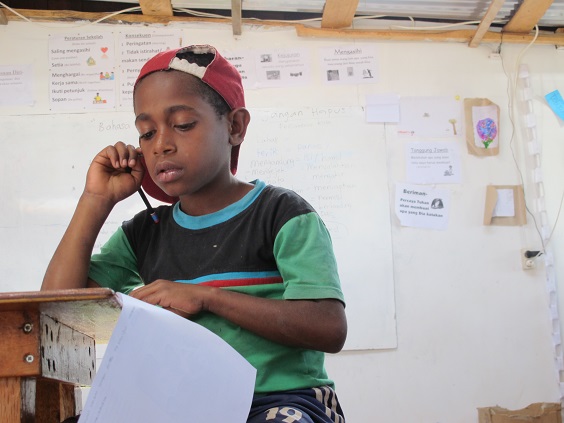

![Anderson 1]() A student at the private Ob Anggen school, Bokondini, Tolikara. Bobby Anderson

A student at the private Ob Anggen school, Bokondini, Tolikara. Bobby Anderson

Under Papua’s 2001 Special Autonomy Law, the majority of Papua’s natural resource wealth is returned to the province. The law was meant to address both the sources of political unrest in Papua, and the challenges ordinary Papuans experience on a daily basis. For example, it was meant to increase Papuan access to government jobs and economic opportunities, as well as to health and education services. A dozen years and billions of dollars later, most Papuans still live in misery: they have the highest malnutrition, tuberculosis and HIV rates in Indonesia; they are the poorest; and they have the lowest rate of life expectancy.

Special autonomy has failed. But the greatest failure has little to do with the aspects of special autonomy that were implemented by Jakarta. Rather, it is the parts of special autonomy that were handed over to provincial and district officials: health and education services.

The autonomy cash cow

Many local officials and elites no longer see special autonomy as a means of development. For them, it is a way to access greater national subsidies, which they can take for themselves or spread through their patronage networks. For the elite, affirmative action is no longer a means to redress the under-representation of Papuans in official positions; instead, it is another way of milking the system. ‘No-show’ jobs have proliferated. Papua now has more than double the number of civil servants that it actually requires. This is an obvious benefit for those who get the jobs, but it has little value for those still locked out.

The failings of special autonomy are enhanced by the uncontrolled creation of new districts, sub-districts and villages under the process known as ‘pemekaran’ (proliferation).. In theory, pemekaran intends to make smaller government entities more accountable. In reality, it simply allows local elites to access funds while pushing ordinary Papuans further away from the services that could improve their lives. Special autonomy has created a dividing line between Papuan elites who benefit directly from it, and the majority of Papuans, who receive a pittance.

In previous articles (Living without a state; The middle of nowhere; Land of ghosts), I have explored particular regions in Papua’s highlands and lowlands. I have tried to bring to light the struggles and concerns of the people who live there – struggles which are divorced from the political discourses that many outsiders mistakenly believe are paramount in the lives of most Papuans. Now I aim to explain how Papuan governments are dealing with their people’s most pressing concerns in the era of special autonomy. In this article, I will discuss how and why the educational system has collapsed in the highlands. I will look at similar failings in healthcare in a later article.

The death of a system

In Papua’s highlands, the interplay of misused special autonomy funding; pemekaran; flawed human resource management; and local understandings of the nature of education, have combined to break the educational system. Almost nobody acknowledges these problems. Instead, a pantomime occurs where many government officials blame the poor education system, lack of infrastructure, or even highland children themselves. Because of this misunderstanding of the problem, the solutions offered are flawed.

Papua’s 2010/11 provincial development plan for basic and secondary education(RPDP) indicates that school enrolment for children aged between seven and 12 throughout the province is 73 per cent. In other words, at least 100,000 out of the 400,000 children in the province are not in school. Junior secondary enrolment is 55 per cent and senior secondary just 37 per cent.

A grimmer and more realistic picture of Papua’s failing educational system in remote areas can be found in Yahukimo, a pemekaran district in the highlands (profiled in my earlier articles, ‘Living without a state’ and ‘The middle of nowhere’). District Department of Education figures indicate that only 18 per cent of children complete primary school there. Worse still, completing primary school is no guarantor of literacy. The majority of highland high school graduates are barely literate.

![Anderson 2]() A newly-constructed and locked up school in Nalca, Yahukimo. No children have ever been in this building. Bobby Anderson

A newly-constructed and locked up school in Nalca, Yahukimo. No children have ever been in this building. Bobby Anderson

A brief history of highland education

Outside of towns and coastal areas like Sarmi, Biak, and Yapen, the failure of Papua’s education system is systemic. This is especially so in the highlands, but it was not always this way. The education system in the Papuan highlands has as its foundation literacy programs founded by various churches and missionary groups beginning in the 1950s. These missionaries studied tribal languages, adapted them to the roman alphabet, and translated the Bible into those languages. Literacy was a tool to spread the gospel, and missionaries took teaching it seriously.

The Dutch rulers of Papua recognised the inability of their colonial administration to provide education to highlanders and so they tasked the churches to do so. They paid teacher salaries on site through these bodies. These missionaries laid the foundations of educational traditions in some mission areas like Pyramid and Ninia, traditions that continue today. They established schools in Wamena and Sentani, which are nowadays some of the best schools in Papua. In these early schools, second-language instruction was in Dutch until 1962. After that Bahasa Indonesia was taught. To ensure standards across institutions, an education coordinating body, the Association of Christian Schools (YPPGI), was founded.

It is important to note that this church-led system never reached the majority of children and youth in rural and highland areas. These were a series of small, well-functioning schools scattered widely in rural areas, with disparate populations of the most remote areas unable to access such services. Most rural Papuans remained out of school. Many children started, but few finished school. Government statistics from 2006 indicate that 56 per cent of the indigenous Papuan provincial population had less than a primary-level education. Twenty-five per cent were illiterate.

After the Dutch departed, the Indonesian authorities kept this arrangement in place at first. In the 1980s, the state began to take over both the schools and the YPPGI. Teachers became government employees, and the schools adopted the national curriculum. At that time, the government also assumed control of the missionary-run health care systems. When the government assumed control of these systems, many in the church felt that they could simply focus on their ‘real’ job of preaching the gospel. However, the government never really took over anything. There was no real process to hand over these institutions. In the best-case scenario, services declined. In the worst case, they stopped. When the churches gave up their social role, their authority also declined.

The education system weakened further at the fall of the New Order regime in 1998, and the beginning of decentralisation. Responsibility was shifted from provincial to district officials, who were unprepared for such a shift. No proper handover occurred, except in titles. The system began to fail in the highlands in 2000, when dozens of killings of migrants in the region led to the flight of most migrant civil servants from the area – medical and school staff among them. The rapid ‘Papuanisation’ of the system under affirmative action was not based on credentials; unqualified persons were slotted into jobs on the basis of their clan affiliations rather than their skills. This was bad enough in existing districts. In new districts created under pemekaran, services collapsed.

Schools aren’t the problem: teachers are

When people speak about problems of education in Papua, they automatically assume that the problem is infrastructure: there must be no schools. This is a false assumption. Papua has an overabundance of schools. Primary school (SD) buildings have increased from 1895 in 2006 to 2179 in 2010; high school/vocational school (SMA/SMK) buildings increased from 159 in 2005 to 272 in 2011. With the exception of Sinokla (profiled in ‘The middle of nowhere’), every remote area I have visited has school buildings. Mostly they are brand new. And locked. Most special autonomy funds spent on education in rural and remote areas go firstly on salaries, and, then secondly on these new buildings. And yet politicians continue to promise to build schools in order to provide education.

With regard to administrative costs, Papua also officially has an abundance of teachers. Provincial records indicate that there are now 15,713 primary school teachers, 6188 junior high school teachers, 3410 senior high school teachers, and 1914 technical high school teachers on the payroll. According to official Papuan documents, the province has one teacher for every 23 students; this is not far from the national average of 18 students per teacher. In the highlands, however, most of these teachers do not show up for work. To say that ‘teacher absenteeism is a problem’ is to pretend that the system functions, albeit with an ‘absenteeism’ handicap. Outside of Papua, ‘absenteeism’ means a teacher might skip a Friday, or not turn up for a day or two within a fortnight’s teaching. In Papua, a teacher might skip a semester. In my research, and in the experience of my colleagues in Papua who work in a variety of state and non-state schools, our observations reveal that most students will attend class when the teacher is physically present. As a consequence, classes with actual teachers are overcrowded, with more than 50 students per class.

We automatically blame teacher absenteeism on the lack of support and facilities available to hired teachers. This is partly true, but the reasons are manifold and vary by area. Even so, some generalisations can be made. Firstly, teachers are not automatically assigned to their areas of origin or residence. Local people in their duty stations often look down upon teachers because they have different tribal or clan affiliations. This can make for an uncomfortable posting.

Secondly, teacher absenteeism does not result in sanctions. Indonesia’s national law on teachers and lecturers, Law No. 14 of 2005, article 30, states that teachers absent from their jobs for at least a month can be dismissed. But enforcement of this provision falls to district officials, who are uniformly unwilling to enforce it.

Third, teachers are not paid on site, nor are they provided with transportation costs reflective of the cost of transport in their assigned areas. They may be paid in a district capital that is an hour’s flight or five day’s walk from their posting. Fourth, their salaries are inadequate. This is often because a portion is siphoned off by the administration before they are paid (this varies by areas: in some areas, this does not occur, whilst in others, the majority of teachers’ wages are mislaid).

A fifth problem is that there are simply no additional support structures in place: a teacher who wants to teach may find himself or herself alone in a school, with no administrators, other teachers or materials. Teachers assigned to remote areas often do not want to relocate their families because there is usually no healthcare in such locations (though there’s often a vicious cycle here: there might not be a functioning healthcare centre because the healthcare workers do not want to relocate because there is no functioning school).

A final problem is inadequate housing. Newly constructed houses for teachers generally disintegrate within a year or two (interestingly, the old missionary homes built in the 1950s still stand).

This litany of problems presents real obstacles. And yet, they cannot explain all of the problems in the education system. Many teachers are local hires, and for them accommodation, transportation, clan ties and separation from families are not issues. Yet many of these teachers are also not teaching. Further, district officials have the power, and the funding, to change this system. If they wanted to, they could hire local teachers, and they have the means at their disposal to pay on site and to fire teachers for absenteeism. They do not.

After wrestling with this issue for months, eventually I realised that the explanation was simple: the people who were given these positions are not actually expected to teach. As I described in ‘Land of ghosts’, local officials, especially in pemekaran areas, award teaching jobs to supporters and clan members. These are no-show jobs, and everybody knows it. The reason why difficulties in duty stations are not addressed is not that people are unaware of the problems. They are not addressed in order to provide people with plenty of excuses not to work. In many places, teachers and school administrators have drawn salaries for years - sometimes for a decade - without showing up for work. In the highlands, the majority of these civil servants who are missing from their remote postings can be found living comfortably in Wamena or the district capitals. Some of the teachers run private childcare centres there.

Seeking solutions

In some instances, governmental and civil society representatives have tried to repair this system. A local NGO offered the district governments of Jayawijaya and Yahukimo a system whereby they would monitor teacher attendance and control salary payments. The heads of both districts accepted the proposition, but then relented, so as not to lose the political and clan support these absentee workers offer. In another instance, the new Jayawijaya head of education stopped the salaries of chronically absent teachers - and those same teachers successfully petitioned the district head (bupati) to reinstate their salaries.

Missionary schools seem to be the only effective schools in the highlands. But they are not generally accredited by local government education authorities. This alternative system represents a threat to absent teachers and administrators within the area, a few of whom run private facilities and therefore sometimes attempt to close the missionary schools. In Bokondini, one absentee teacher runs a for-profit private school across the street from the government school where she is supposed to teach, but has not set foot in for years. Ironically, her own children are enrolled in the nearby missionary school set up by outsiders as an alternative to the failing system which she is a part of. This is good insurance for the missionary school; that same teacher once advocated the closure of the missionary school because she viewed it as competition to her for-profit business.

A flawed solution to tough conditions for teachers in the highlands can be found in boarding schools: a few in Wamena and Sentani offer superior education, and some missionaries and local officials advocate increasing the numbers of private institutions where children may be sent. But these entities are private institutions that provide high quality education for a minority of children whose parents can pay for it. Scaling up the schools would mean broadening the pupil base, which would require lower fees or state subsidies in the form of scholarships. This would require increased class sizes, more teachers, expanded facilities, and the agreement of private administrators who rightfully fear that ‘scaling up’ will result in a decline in the quality of services. Other private institutions would not offer anywhere near the quality of the original institutions. It is also unrealistic to expect the state to be able to create a new layer of elite schools, given the performance of existing, non-boarding schools.

In addition to boarding schools in the province, there are also institutions outside Papua. For example, Jakarta’s Surya Institute takes children from Tolikara and other areas of Papua and trains them intensively in maths and science. This approach has produced children who win at international mathematics competitions, helping to break the stereotypes that many outsiders have about Papuans. But it’s an approach that comes with a price. Encouraging Papuans to send their children away in their formative years breaks their connections with their families and communities.

More common than boarding schools is the practice of unaccompanied children trekking long distances to places with functioning schools. Wamena is full of ‘student hostels’, each owned by a church from a specific highland area, where children who have travelled to Wamena to enroll in school may stay. However, these hostels are generally used as flophouses for anyone from the area of origin. They are public health threats, with no supervision, open defecation on the grounds, and no running water. As well as being transmission centres for tuberculosis, they are unsafe for children, especially girls, and rapes commonly occur in them. Drug use, especially the inhalation of solvents, is also alarmingly common in such hostels.

![Anderson 3]() The functioning school in Nalca, Yahukimo. Classes are taught in a church: teachers are unaccredited and unpaid. Bobby Anderson

The functioning school in Nalca, Yahukimo. Classes are taught in a church: teachers are unaccredited and unpaid. Bobby Anderson

Contextual curriculums?

Another flawed solution offered to fix problems of education in Papua can be found in the drive for ‘contextual curriculums’ (‘kurikulum kontekstual’ or ‘kurikulum khusus’) in Papuan schools. The need for such curriculums is frequently mentioned by state education officials, local NGOs and donors. Such curriculums have value when they focus on language. Indigenous Papuan children do not speak Indonesian at home, although they do tend to pick up plenty of Indonesian vocabulary before they first enter primary school. The first day of school in a functioning curriculum that uses only Bahasa Indonesia is a daunting one for indigenous children. They immediately find themselves at a disadvantage to the children of migrants who speak Indonesian at home.

One foundation in the Highlands, Yayasan Kristen Wamena (YKW), identified roughly 1000 Indonesian words that local children were familiar with and built a first and second-year curriculum in mathematics and Indonesian based upon these words. Some of this curriculum was also in Dani. This YKW curriculum was aligned to national standards, and the response of local children to it was extremely positive. They were less intimidated and advanced faster. This curriculum has since been adapted in numerous highland districts. But in remote areas, the books produced by YKW risk becoming food for silverfish, because the core problems of human resources remain.

Many proponents of a contextual curriculum take their argument too far. They say that the national curriculum does not account for the Papuan ‘context’, and that children cannot relate to what is being taught, and so they lose interest. It is as though images of ‘straight-haired’ children and unknown machines such as ships and trains are such a turn-off for Papuan children that they simply walk out of the classroom to go and play with rocks. Such an argument would be laughable if it did not have a disturbingly racist undertone. What’s even more disturbing is how often such arguments are made by Papuan teachers and administrators. By the same argument, one could eliminate from a curriculum everything not visible to the naked eye: planets, bacteria, even history beyond living memory. Highland children are like children the world over: innately curious sponges that absorb the information which fascinates them. The real issue is not their capability, but what they are being denied by a failing system.

A flawed understanding of education

In rural Papua, parents and children tolerate this system because all too many of them do not have an adequate concept of what classroom education is intended to impart. They have never seen a functioning state school. Of the older highlands generation, a majority did not have access to the limited church-led system. They are illiterate and had minimal or no schooling. For illiterate parents, education is not the acquisition of practical knowledge through systematic instruction. Instead, it is just one more supernatural key to advancement and wealth in an animistic belief system full of such devices. It is possessed by the teachers, and its acquisition is purchased from the teacher over time by means such as ceremonies and gift-giving, rather than by study.

This is how it looks to many parents in rural areas: Parents send their children to school. The children show up to a building once a week or less, at the appointed time. They then go home, more or less straight away. There are no classes: anyone who has spent time in the highlands marvels at the school grounds filled with kids in ratty uniforms playing football, with not a teacher in sight. Every so often a teacher issues a demand: ‘bring firewood’, or ‘bring cigarettes’. The parents provide the children with these items to take to school. At the end of the year, the state test is given. The teacher writes the answers on the board for the children to copy (I have peeked through the dusty, bird dropping-spattered windows of numerous rural highlands schools and seen the answers written on the board from the last tests administered; no one has been in the schools since), or the teachers fill out the exams themselves. The students then go on to the next year.

Finally, upon graduation they receive the diploma - a piece of paper certifying to parents and students that education has been transferred. The diploma is all-important: it allows the graduate to obtain a coveted civil service job, where, in the words of one young man in Bokondini, one ‘never has to work again’. People take the issuance of these diplomas very seriously. An attempt to fail a child is likely to result in threatening visits by that child’s parents.

This process ends with high school graduates who cannot read, write or perform basic mathematics. Universitas Cenderawasih (UNCEN, the best university in the Papua region) maintains a list of the worst schools in Papua, and refuses to consider anyone with a diploma from these schools for entry. Other post-secondary schools are not so discriminatory: this systemic fraud continues through technical and other post-secondary schooling. It then results in illiterate graduates who sometimes go on to become illiterate teachers and administrators.

Many post-secondary institutions report that, on average, young adults from rural areas entering their systems read at a primary school second to third-grade level. In other words, they have received the equivalent of three years schooling over a twelve-year period of education. A Christian teacher’s college (STKIP) outside of Wamena provides one and a half years of intensive remedial literacy and numeracy classes for every student before the real curriculum begins; all of them need it.

Another NGO working in Yahukimo recruits young Papuan adults to act as teachers’ assistants in rural schools with absentee teachers. These assistants, all volunteers, require basic instruction in mathematics and literacy. And yet they are so eager to learn that four weeks of intensive classes can advance them through four years of primary education. The intellectual hunger and passion for self betterment that these young people display flies in the face of the ‘Papua’ stereotype, and makes the failure of the education system all the more unforgivable.

Given most students (and their parents) are not aware they are being cheated out of an education, it can be a shock when they are confronted directly about their lack of educational achievements. And this does sometimes happen. Motivated teachers still enter this system. They attempt to teach, and in their classrooms, students who do not study face consequences. But when those teachers fail students, they are often threatened by parents angered by the violation of the assumed agreement of exchange. School buildings have been burned because of such failures. Such idealistic teachers either surrender to the system, or they leave. Many of them go to work in the parallel private and missionary systems, where they are paid little. The irony of paid teachers not teaching while volunteers teach for a pittance, and sometimes nothing at all, is found all across the highlands.

In many parts of the highlands, alternative groups are fulfilling the demand for education. Yasumat, a local foundation that specialises in education, health, and governance, teaches in half of the sub-districts in Yahukimo. Narwastu, another NGO, is staffed by long-term volunteers from North Sulawesi. It provides the only education in Binime, Memberamo Tengah. Parents have become so enthusiastic about what their children are learning in this organisation’s schools that Narwastu has created evening classes for the parents. Ob Anggen, a school in Bokondini, Tolikara, offers an education that may be the best of its kind, not just in the province, but in all of eastern Indonesia. The success of these private institutions makes the failure of nearby state schools less tenable. Local parents, in Bokondini and elsewhere, are beginning to get angry at what they are slowly recognising to be fraud.

These foundations and church groups aren’t the only ones filling the education gap left by the state. In another lowland area outside of Jayapura, Holtekamp, the hardline Islamist group Hizbut Tahrir has established two schools. Their teachers are dutifully teaching over a hundred indigenous and migrant students every day.

![Anderson 4]() Volunteer teachers in a Yasumat school, Ninia, Yahukimo. Bobby Anderson

Volunteer teachers in a Yasumat school, Ninia, Yahukimo. Bobby Anderson

Solutions

Fixing this broken system must involve an acknowledgement of what the real problems are. And there are no ‘quick fixes’ in the repair. Buildings are not needed. What is needed is teachers who teach, and district administrators who actually manage schools. The Law No. 24 provisions about teacher absenteeism need to be enforced, possibly retroactively. In the feudalistic structure erroneously called ‘decentralisation’, district heads are all-powerful. They need to be divested of the right to influence human resources in district schools. It’s one thing to award no-show jobs in the civilian bureaucracy, where the salaries of such people simply suck funds from the system, but no-show educators – and healthcare workers – do real harm. Such positions should be considered off-limits in local patronage games.

Contextual curriculums can be useful, but only with teachers to teach them. Anyone who continues to blame Papuan children for their lack of education must simply be ignored. Teachers who do this should be fired.

In 2012, Cenderawasih University and the provincial education office created a draft provincial regulation to clarify roles and responsibilities in the education sector. The draft includes scholarships for indigenous students; vocational and technical training opportunities; employment of local primary teaching assistants in remote areas; and additional support to teachers in remote areas.

This draft is a start, but it neglects to address the core cause of the failure of the educational system: ineffective management of human resources. It does not talk about criteria for hiring teachers; the need to dismiss teachers who are not teaching; and the consequences for administrators who do not act against absentee teachers. Until this issue is acknowledged, all other approaches to the problem will remain ineffective. And children and youth in these areas will continue to be cheated.

New teachers need to be hired, and paid, locally. Additional support for teachers in remote areas should only go to new teachers or ones who have a record of attending their schools. Providing teachers who have not taught with additional support in the hope that they will now teach is not a good idea. This broken system cannot be fixed if such persons remain within the system, and are bribed for their neglect rather than punished for it.

Local youth and adults with the ability to read and write at a higher functional level than usual in their area can be trained as assistant teachers. They can then be responsible for the education of primary students, and older students not yet functioning at the primary level. A six-month or one-year training course for such candidates would suffice. We need to leave computers and English and science for later, and start with the core foundation of education: reading, writing, and mathematics. Teaching must be in Indonesian and local languages, and utilise a linguistically contextual curriculum such as the one developed by YKW.

During an interim period of repair of the state system, one option for provincial and district authorities would be to formally recognise the parallel institutions that were created to address the education gap. In areas where state schools are not functioning, such private institutions need to be accredited (as long as they teach the national curriculum).The volunteers who usually teach in such systems could be put on the government payroll, but paid through the churches and other private institutions that run the systems.

It is important to remember that citizens are made in schools. Indonesians do not just learn reading, writing, and mathematics in school: they learn about Pancasila and what it means to be an Indonesian, the history of the state and the struggles of its founders. Such lessons are a counter to radicalism, whether it is of a religious or separatist variety. In a place where functioning schools are few and far between, and are usually private, is it any wonder that such a concept of citizenship is lacking?

Bobby Anderson (rubashov@yahoo.com) works on health, education, and governance projects in Eastern Indonesia, and he travels frequently in Papua province. The next article in his series will focus on the failure of healthcare in the highlands.

Other articles by this author from the II archive

Living without a state, 110 (Oct-Dec 2012)

The middle of nowhere, 111 (Jan-Mar 2013)

Land of ghosts, 112 (Apr-Jun 2013)

No-take zones, 112 (Apr-Jun 2013)

Inside Indonesia 113: Jul-Sep 2013{jcomments on}

![purdy1]() Hannah Purdy

Hannah Purdy

Since East Timor voted for independence from Indonesian rule in 1999, the country has wrestled with the best ways to account for past human rights abuses, in particular those that occurred during the Indonesian occupation from 1975 to 1999. In 1999 alone, over 1000 people died in the lead up to and following the UN-sponsored referendum to separate from Indonesia.

Since East Timor voted for independence from Indonesian rule in 1999, the country has wrestled with the best ways to account for past human rights abuses, in particular those that occurred during the Indonesian occupation from 1975 to 1999. In 1999 alone, over 1000 people died in the lead up to and following the UN-sponsored referendum to separate from Indonesia. This is a delicious book – to be savoured, appreciated for its richness of detail and admired for its texture and cohesion. It made me greedy for more. I thought I could just dip in and read it over a week or so (it is a lengthy tome) but I was drawn into it from the first page of the Preface and just kept reading.

This is a delicious book – to be savoured, appreciated for its richness of detail and admired for its texture and cohesion. It made me greedy for more. I thought I could just dip in and read it over a week or so (it is a lengthy tome) but I was drawn into it from the first page of the Preface and just kept reading.

If Australia has been blessed with excellent cartoonists, Indonesia has been similarly blessed with excellent columnists. Thanks to Jennifer Lindsay’s translations, English-speaking readers outside Indonesia can appreciate Goenawan Mohamad’s ‘Catatan Pinggir’ (Sidelines) columns from Tempo magazine.

If Australia has been blessed with excellent cartoonists, Indonesia has been similarly blessed with excellent columnists. Thanks to Jennifer Lindsay’s translations, English-speaking readers outside Indonesia can appreciate Goenawan Mohamad’s ‘Catatan Pinggir’ (Sidelines) columns from Tempo magazine. This is a brilliant book, a must read for anybody wanting to understand the Asian city. In Indonesia, kampung dwellers make up over half of the urban population. Peters sees Surabaya from the alleyways of Dinoyo, a poor inner-city kampung.

This is a brilliant book, a must read for anybody wanting to understand the Asian city. In Indonesia, kampung dwellers make up over half of the urban population. Peters sees Surabaya from the alleyways of Dinoyo, a poor inner-city kampung.

Search for ‘how to cheat’ in the British GCSE or American SAT exams and you’ll get lots of hits too. But most coverage of cheating in such countries is of the breathless ‘how a small minority gets away with murder’ type. Typical Indonesian headlines include: ‘When collective cheating becomes a tradition in the national exams’ and ‘Cheating as Academic Culture.’

Search for ‘how to cheat’ in the British GCSE or American SAT exams and you’ll get lots of hits too. But most coverage of cheating in such countries is of the breathless ‘how a small minority gets away with murder’ type. Typical Indonesian headlines include: ‘When collective cheating becomes a tradition in the national exams’ and ‘Cheating as Academic Culture.’

For Indonesia, 1965 is a year which remains shrouded in darkness. To use Goenawan Mohamad’s term, is a titimangsa; a ‘black hole’ which symbolises the establishment of the power of Suharto’s New Order, the beginning of a period which spelled the end of the ongoing political chaos. According to the New Order’s official version of history, 1965 is synonymous with the successful eradication of an unwanted ideology.

For Indonesia, 1965 is a year which remains shrouded in darkness. To use Goenawan Mohamad’s term, is a titimangsa; a ‘black hole’ which symbolises the establishment of the power of Suharto’s New Order, the beginning of a period which spelled the end of the ongoing political chaos. According to the New Order’s official version of history, 1965 is synonymous with the successful eradication of an unwanted ideology.